Draft Final Report: Public Hospital Excavation October 1981-January 1983 Archaeological Report Block 4 Building 11Draft Final Report: Public Hospital Excavation October 1981-January 1983

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report

Series - 0144

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

DRAFT

FINAL REPORT PUBLIC HOSPITAL EXCAVATION

OFFICE OF EXCAVATION AND CONSERVATION

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

MAY 1983

INTRODUCTION

The following report is a review of the archaeological excavations that were conducted at the Public Hospital site from October 1981 through January 1983. The fifteen-month period covers the time that I took over the supervision of the field excavations from Mr. John Hammant, until the project came to a close at the end of January 1983. The report does not exclusively describe archaeological features that were discovered while I was in the field, but also includes a few that were uncovered while Mr. Hammant was supervisor. For instance, Mr. Hammant was working on the 1825 kitchen complex and the structure on the east slope of the ravine when he was assigned other duties, making it necessary for me to continue both excavations.

The report describes five major archaeological features and structures; namely, the 1825 kitchen complex, the late eighteenth/early nineteenth-century kitchen, the small structure on the east slope of the ravine, the south boundary line and the Jones/Nicholson layers. These features were considered to be the most important of those investigated during the period mentioned above.

The 1825 kitchen served as one of the major support buildings for about 45 years and a study of the evolution of the structure was deemed to be important enough to warrant a lengthy investigation. The late eighteenth/early nineteenth century kitchen was important because it may be one of the earliest outbuildings associated with the hospital. Another support building was found on the east slope of the ravine. While its exact function could not be determined, heavy concentrations of bones found during the excavations suggest that it may have been used as a meat house. A series of post holes found on the east side of the site were interpreted to be the south boundary line. The boundary line established the limit of the hospital property north of Ireland Street. The Jones/ Nicholson layers were equally significant since they represent the earliest occupation of the property. The pre-hospital layers were very extensive and were examined by all three supervising archaeologists.

This report is the last of three reports on the Public Hospital excavations, the first two having been submitted by Messrs. Luccketti and Hammant.

EXCAVATION OF 1825 KITCHEN COMPLEX

Food preparation at the Public Hospital appears to have taken place, for the most part, in two buildings near the southwest corner of the main structure. Historical records indicate that there were two separate kitchens in this vicinity, a fact substantiated by archaeological excavations. The remains of two separate kitchen-related brick foundations were discovered, each dating from different periods. Historical documents are somewhat vague, but archaeological evidence suggests that the first kitchen structure may date from the latter part of the eighteenth century. Dating the second kitchen archaeologically proved more difficult. Fortunately, written sources were more explicit about the later kitchen and date its construction to 1825. Documentary evidence indicates that, for a brief period, use of the two kitchens overlapped.

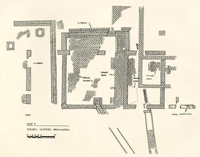

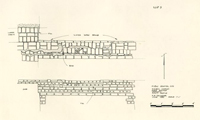

Portions of the 1825 kitchen were first uncovered on March 11 and 12, 1981. Sections of brick foundation were exposed as heavy machinery scraped away upper layers of modern fill near the southwest corner of the original building. A two-brick-wide structure, with dimensions of 15 by 21 feet, was found containing what appeared to be destruction debris.

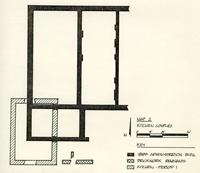

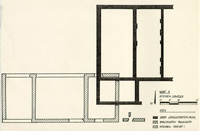

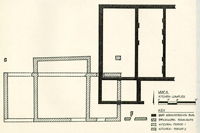

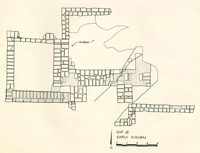

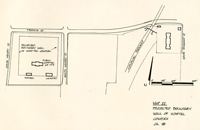

Clearing operations uncovered two additional brick 2 features. The extreme west foundation wall of the 1885 Administration Building cut the northeast corner of the kitchen, while another section of brick foundation lay outside the southeast corner (see map #2). The section of brick wall near the southeast corner appears to have been disturbed in the construction of the kitchen and, therefore, predates that structure. The presence of the 1885 Administration Building foundation indicates that the kitchen was no longer in use by that time.

The extent of the kitchen was initially thought to be contained within the limits of the 15 by 21-foot foundations; however, subsequent excavations proved otherwise. Archaeological excavations to the west of the kitchen in May 1981, revealed additional brick features associated with the building. The actual exterior dimensions of the kitchen measured 50 feet 6 inches by 21 feet. The foundation uncovered in early March 19$1 belonged to the east room of a three-room kitchen structure (see map # 3).

The brick kitchen is thought to have been built sometime in 1825, but probably no later than the first week of January 1826. The first documented reference to the kitchen is dated June 14, 1825, At that time, the directors of the hospital "Ordered that Roscow Cole Treasurer of the Hospital pay to Thomas C. Lucas the undertaker of the building of a New Kitchen and 3 other improvements to the Hospital, the sum of Seven Hundred and Ninety seven dollars and Eighty three & 1/3 Cents in further payment of his Contract for said buildings reserving the sum of Three hundred dollars until the said work shall be Completed and received by the Court." 1

On January 5, 1826, the directors ordered that Thomas C. Lucas be paid "in full for his contract for building a New Kitchen..." 2 Six days later, on January 11, 1826, A. D. Galt, president of the Directors of the Lunatic Hospital, mentioned in a report to the Speaker of the House of Delegates of Virginia that "a large brick kitchen" had been built out of the annual appropriations of 1825. 3 Both sources indicate that the kitchen must have been completed by the first week of January 1826, if not sooner.

The directors of the hospital apparently decided to change the specifications for the kitchen, informing Thomas C. Lucas on June 14, 1825, "to runing the new B kitchen wall one foot Higher than it was to be in the foundashon two Bricks thick..." 4 It's assumed that the "new B kitchen wall" actually means the new brick kitchen wall. This description of the kitchen is significant because the building uncovered in March and May 1981 contained foundations that were two bricks wide.

4The actual size of the kitchen was never mentioned in any of the above sources; however, Mutual Assurance Society policy #6023, dated January 5, 1830, described it as a 50 by 28-foot structure. 5 The insurance policy further states that the kitchen was a one-story building covered with wood. The dimensions of the building described in the insurance policy closely correspond to the measurements of the foundation uncovered in 1981, but with some variations. The length of the exposed foundation measured 50 feet 6 inches, while the insurance policy states that they were 50 feet. This is a slight difference of only 6 inches. On the other hand, the width of the original foundation was 21 feet, but the insurance policy lists 28 feet, a difference of 7 feet. This difference of 7 feet cannot be explained. The insurance policy may have taken into account a porch attached to the front of the kitchen, but there are no historical documents, nor any archaeological evidence to support this assumption.

At a later date, an attachment was built onto the original kitchen and, taking this into account, the total dimensions of the structure would have been 50 feet 6 inches by 28 feet (see map #4). However, there is documentary evidence which suggests that the addition was not built until after 1835, five years after the Mutual Assurance Society policy #6023 was issued.

5Insurance policies cannot be relied upon too heavily for accurate information. This is evident from the Mutual Assurance Society policy #11,264, dated January 25, 1843, which gives the dimensions of the kitchen as 50 by 24 feet. 6 The kitchen addition was believed to have been in existence by that time and, as previously mentioned, the dimensions were 50 feet 6 inches by 28 feet, not 50 by 24 feet. While there is room for skepticism about the width of the kitchen, the insurance policies are consistent about the length.

The remodeling of the kitchen probably took place about 1835. According to a report prepared by a committee appointed by the House of Delegates to examine the state and condition of the hospital, "$12,000 will be necessary for the support of the hospital at Williamsburg for 1835," and out of that amount, $1,500 was needed for "building two culverts and addition to the kitchen." 7 Two culverts (vaulted brick drains?) and an addition were uncovered in May 1981.

Other features added to the interior of the kitchen during the remodeling were a large brick hearth base, a brick floor, and a drain box which emptied into one of the vaulted drains. Exterior changes included a brick walkway, a V-drain to carry off water, window wells, and other unidentified structures (see map #5).

6The 1825/1835 kitchen complex was probably demolished by the early 1870s when a larger kitchen-chapel was built to replace the older structure. Part of the kitchen-chapel foundation, along with a large cistern, cut through the western end of the earlier kitchen during construction (see map #5).

1825 KITCHEN INTERIOR

Prior to extensive excavations, modern layers concealing the kitchen were mechanically removed to save time and effort. Mechanical excavations were halted when brick foundations and other related features began to appear. The more recent activities had to be cleared before any investigation of the building could begin. Builder's trenches for the 1885 structure and the 1870s kitchen-chapel were removed along with post holes and utility trenches that postdated the kitchen.

More foundations were discovered when the modern intrusions had been cleared away. A partition wall, dividing the west and central rooms, was found at the bottom of a robber trench. In addition, a small section of the original north wall was exposed when the robber trench fill was removed. The north wall and the partition were apparently built at the same time, as shown by their interlocking construction. The west wall of the 1835 addition was also exposed when the robber trench was excavated. The addition abutted the original north wall, showing that it was built at a later date.

A diagonal utility trench cutting the central room contained another section of the original north wall. The two 8 sections of wall exposed in the diagonal trench and the robber trench lined up with the return at the northwest corner of the kitchen foundation (see map #5 ).

The rubble from the demolition was found only in the east room of the original building and it is here that the archaeological investigation of the kitchen began.

The destruction debris contained a mixture of red and orange bricks with large chunks of mortar. Most of the bricks were either whole or in large pieces. The brick rubble had been cut by the builder's trench for the 1885 Administration Building (E.R. 2553A-4.C.) and a 3-foot wide north-south trench (E.R. 2553C-4.C. and E.R. 2553D-4.C.) The 1885 foundation and the north-south trench broke through the kitchen walls, indicating that this activity had taken place after the building was destroyed.

The presence of the red and orange colored bricks is significant, because it appears to be one of the distinguishing features between the original brick work and the later additions. The original kitchen contains bricks that are, for the most part, orange in color, while the remodeling was done with red bricks.

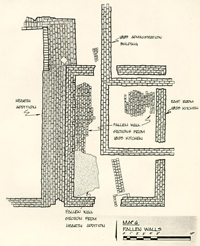

Beneath the loosely-packed rubble were two 3-foot wide sections of articulated brickwork lying against the west wall of 9 the east room (see map #6). Upon closer examination, it was determined that one of the brick walls was part of the kitchen hearth (E.R. 2553F-4.C.). The bricks, laid in Flemish bond, were reddish in color and showed evidence of burning. The thickness of the articulated brick work was 2 feet 4 inches, which is about 11 inches wider than the original foundations.

A whole wine bottle and fragments of a metal bucket (E.R. 2553F-4.C. #1) were found while dismantling the fallen hearth. The bottle and bucket fragments were partly sealed by the rubble. Obviously, the bottle was inside the bucket which prevented it from breaking when the building was brought down. The bottle most likely dates from the first quarter of the nineteenth century and did not aid in dating the destruction of the kitchen, since it predated the remodeling. The presence of whiteware found among other artifacts from the debris dates the demolition after 1840.

Another section of articulated wall (E.R. 2553H-4.C.) was found partially sealed by the hearth (see map #6). It, too, was laid up in Flemish bond, but was constructed of nine courses of orange bricks. It appears that this brickwork is the upper west wall of the east room.

When the kitchen was remodeled, the hearth base was built abutting original foundation (see map #5). The west wall 10 was probably used as additional support for the chimney. Apparently, when the kitchen was destroyed, the hearth and the west wall were either pushed or pulled into the east room. This would explain why remnants of the chimney were lying on top of the orange brick wall.

The bonding pattern, of what is thought to be the original west wall, was interrupted by a brick windowsill (E.R. 25536-4.C.). The sill was constructed of four header bricks. Above the sill was an open space in the wall which measured 2 feet 4 inches in length. The open space is probably where a window would have been (see map # 6). The brick sill was cut when the 1885 Administration Building was constructed. The fill from within the possible window space contained a great deal of broken glass. One piece still had the putty attached to the edge. The glass strongly suggests that a window was placed on this wall.

Another section of articulated brick wall was found along the inside edge of the east wall (E.R. 2556-4.C. - see map #5 ). The wall contained fourteen courses of brick and measured about 4 feet in length. It is probably a section of the upper east wall. It, too, was composed of orange colored bricks and was laid in Flemish bond.

The hearth-related brick work and the two orange colored sections of articulated walls are the only surviving 11 portions of the kitchen that may have stood above ground. The walls fell into what appeared to be a cellar.

1825/1835 KITCHEN-CENTRAL ROOM

The excavations then shifted to the central room with emphasis on the brick floor. The brick floor was found only in the central room, extending from the north wall to the south wall and abutting the hearth base. It is not known if the floor extended beyond the partition wall because the west room was heavily disturbed by the 1870s construction activity.

The floor was laid with whole bricks and an occasional half-brick. The bricks were dark greyish-red in color, and were unlike those used in the construction of the kitchen or the north addition.

The floor had been cut by a modern utility trench leaving a triangle of brickwork in the northwest corner of the central room relatively intact. Southeast of the diagonal trench, the floor had been disturbed by a large tree and only scattered sections were left (see map # 5).

The bonding pattern became irregular near the north wall of the addition, where it appeared that some type of 12 remodeling or repair work had taken place. Apparently, the floor had been taken up in this area and replaced with a completely different type of brick when the work was finished. The first three to four courses of the brick floor ran parallel to the north wall, but the next few courses sloped toward the southwest (see map #7 ). The replacement bricks were softer and smaller than those in the floor to the south. Most of the bricks were either deep red or purple in color. Obviously, the filler bricks did not fit properly which may have caused the irregular alignment of the floor.

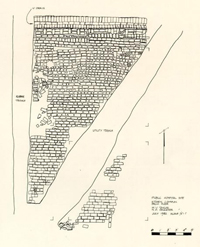

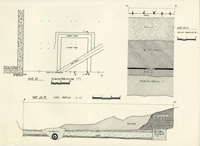

A ¾ to 1 ½-inch layer of brown sand was used as a leveling agent for the floor. A layer of white sand was found beneath the bricks where the irregular alignment occurred. Evidently the white sand was put down on top of the brown sand after the repair or remodeling was finished. While the brown sand ran up to the edge of the north wall, the white sand was found covering a 5 ½ inch wide section of the foundation. Looking at the profile (see map # 8), it would appear that the north addition foundation was purposely built with a step or platform to accommodate a floor.

A remnant of a doorway in the middle of the north addition foundation could still be seen (see map #9 ). The foundation appears to have been cut either to repair an existing door, or to put in a new one. A thin layer of grey sand mixed with ash 13 and flecks of brick, charcoal, and mortar was found lying on top of the brown sand. The grey sand layer was located only in the vicinity of the doorway. The impression is that a section of the floor had been taken up near the doorway when the repair or remodeling activity took place and the grey sand layer was the debris left behind when the work was finished. A layer of white sand was then put down to seat the new section of brick floor.

The floor of the east room appears to have been wood. The presence of slots cut into the west wall of the east room would suggest that floor joists once spanned the foundations (see map #5). The slots are about 3 feet from the bottom of the foundation, which would hardly qualify for a cellar space. If a cellar had existed in the east room, then the slots would have been cut into the foundation during the remodeling phase. The slots and the brick floor in the central room are on approximately the same elevation.

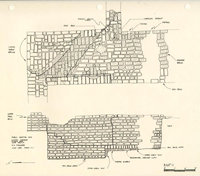

Water was carried off from the east room foundation by a vaulted brick drain that entered the south wall (see map #5 ). The bonding of the south wall may indicate that the vaulted drain predates the 1825 kitchen. The south wall looks as if it were built on top of the existing drain (see map #10). If the vaulted brick drain predates the building, it is possible that it was used to carry away water from the unknown structure located outside 14 the southeast corner of the kitchen (see map #2). However, there is no archaeological evidence to suggest that this was the case.

The slots may have been purposely cut into the east room during the construction in 1825. By placing the floor above ground level, it would allow the drain to continue to carry off water from the foundation.

In 1835, it was mentioned that two culverts or brick drains were to be added to the kitchen. One of the drains is thought to have been uncovered at the south wall of the central room. The drain originated inside the central room in the form of a square box. Water could be dumped into the drainage box and carried off down the vaulted drain without ever leaving the building.

The drain box was composed of red bricks bonded together with sand mortar. It was built against the south wall where the vaulted brick drain entered the kitchen (see map #5 ). The drain box probably had some type of covering at one point. The top of the drain was level with the floor, which had been laid neatly around the edges.

Nothing was recovered from the builder's trench which could solidly date the construction of the drain. A great deal 15 of charcoal and fish bones were found in the bottom of the trench.

Below the brown sand leveling agent used to seat the brick floor was a thin layer of brick and mortar flecks and dust about ¼ to ½ inch thick. This layer is probably debris from the remodeling period.

The brick and mortar layer was concealing some redeposited clay. The redeposited layer was composed of a mixture of yellow, red, and orange clays about ½ to 5 ½ inches thick. Obviously, the layer of clay was disturbed and brought in from elsewhere. In any case, the clay was used as a base to support the heavy brick floor.

When the redeposited clay was removed, a thin layer of red and orange brick dust was found scattered around the area. The red brick dust was found between the two north foundations, while the orange dust was south of the original north wall (see map # 8). The removal of the dust layers exposed builder's trenches and robbing activities that took place during the life of the kitchen.

The date of the hearth base is not known with any certainty, but is believed to have been built at the same time as the 16 north addition. Evidently the builder's trench for the hearth base had cut through an earlier layer because the artifacts found in the excavation dated after 1770. The base measured 9 by 28 feet and abutted the west wall of the east room (see map #5 ). The massive size of the hearth base implies that it supported more than one fireplace. If the remodeling of the kitchen had been part of an effort to support the increasing number of patients, it stands to reason that more than one cooking fire would have been needed. Scattered patches of scorch marks were found on the base when it was first uncovered.

Near the north wall of the kitchen, a 6-foot long section of the west face was missing. An area one brick wide and at least eleven courses high had been removed from the base (see map #11). The mortar on one of the overhanging bricks was molded in a manner that would suggest corbelling. However, there were no other architectural features that could verify if there was any corbelling on the hearth base.

The east wall of the addition was used as part of the hearth foundation. While the width of the west and north walls were two and a-half bricks, the east wall, which included the hearth base, was 9 feet wide. The foundation of the addition is approximately 10 inches deeper than that of the hearth base. A 7 foot 6 inch section of the hearth that was built into the 17 east wall of the addition is also 10 inches deeper than the remainder of the foundation (see map #11). The change in the depth of the foundation occurs where the east wall abuts the original north wall of the kitchen (see map #11). South of the original north wall, the hearth foundation is 10 inches higher.

The construction of the hearth involved the use of both orange and red bricks. The hearth base was the only brick feature in the kitchen complex that used two different colors of brick. For the most part, the bonding pattern was not unusual. Flemish bond was used as it was throughout the kitchen. The exception was the bottom course of bricks where the foundation was 10 inches higher. Here, the bricks were laid in row lock fashion (see map #11). The row lock and the next four courses above it were done in red brick. Six courses of orange colored bricks were laid on top of the red brickwork. A row of red bricks then covered the orange ones (see map #11).

The orange bricks were very similar to the original brickwork and may have been part of the north wall that was obviously brought down during the remodeling period. In order to economize, the orange bricks may have been used as filler. All of the orange bricks were placed below ground level, probably so they could not be seen.

The builder's trenches for the north addition were relatively undisturbed by later construction activities. The 18 builder's trench inside the kitchen extended about 4 feet from the addition foundation. The trench gradually sloped toward the wall and then dropped sharply to the bottom (see map #8). The width of the builder's trench was 4 feet at the top and 3 inches at the bottom. The overall depth was 3 feet 2 inches. The fill of the builder's trench was divided by a thin layer of red brick dust. The red dust layer began at the outer edge of the trench and continued down the slope about 1 foot 3 inches from the top (see map # 8). Almost 2 feet of builder's trench fill was found beneath the red brick dust.

About 2 feet from the bottom of the foundation there was a change in the thickness of the wall. The width of the wall decreased by more than an inch. The red brick dust layer was found where the structural change occurred (see map #8 ). It would appear that the builder's trench was partially filled in while the addition was under construction. The red brick dust was probably debris left as the work on the wall continued.

The exterior builder's trench extended about 6 feet from the north face of the wall. It began as a lense and gradually sloped toward the wall to a width of 7 inches. The overall depth of the trench was approximately 3 feet 6 inches. The layers in the trench correspond roughly to those found in the builder's trench inside the kitchen (see map #8 ). The trench was filled 19 with two layers of redeposited material separated by a layer of red brick dust. The red brick dust layer in the north trench is thicker and about 5 inches higher than the layer of dust found on the other side of the wall. The 1 inch indentation on the south face was not found on the north side of the wall.

Wood planks about 1 inch thick were found beneath the west and north walls. The planking had apparently been used to seat the foundations. There was no evidence of wood planking beneath the east wall and the hearth foundation.

Artifacts from the south side of the wall date after 1770, while the trench along the north face contained material with a terminus post quem of 1820. Obviously, the trench for the north addition had cut through earlier or pre-kitchen layers.

The north wall in the central room of the 1825 kitchen was torn down during the remodeling. Before major excavations began, two small sections of the original wall were exposed when the modern features had been cleared from within the kitchen. The robber trench and builder's trench for the north wall were concealed by the layers used to support and level the brick floor. Approximately 13 feet 6 inches of the robber trench had been left undisturbed. The trench was 2 feet 4 inches wide.

20During the robbing activity, a 6-foot long section of the wall remained relatively intact. The wall, which was partially dismantled, contained orange colored bricks laid in Flemish bond. Artifacts recovered from the excavation of the trench date after 1790.

The robbing of the wall did little damage to the builder's trenches. The south trench was 2 feet wide at the surface and narrowed to one foot near the bottom of the wall. The trench fill was from 4 inches to 2 feet 8 inches deep. The north trench was 2 feet 1 inch wide and had vertical sides. The bottom gently sloped toward the wall and then dropped sharply until the trench was only ½ to 2 inches wide (see map #8).

The height of the remaining section of the north wall was 2 feet 9 inches from the base. It was cut at the east end by the construction of the hearth base and east wall of the addition. The west end was disrupted where the partition and the west addition wall meet.

The builder's trench along the south face of the north wall began to widen by about 7 inches as it neared the hearth base (see map # 8). The hearth base was dismantled in an attempt to follow the line of the trench, but most of the feature had been obliterated during the remodeling of the kitchen. When the fill was removed from the trench, no brick work could be found; 21 presumably, the entire wall was robbed out in this vicinity. There were no other architectural or archaeological features that could provide any clues as to the reason for the difference in the width of the trench.

The north wall was thought to have been cut where the partition wall divides the east and central rooms. The northwest corner of the east room was expected to show some evidence that there was a break in the bonding of the wall. However, when the hearth base was dismantled, it was clearly visible that the north wall of the central room was never bonded into the north wall of the east room. The northwest corner of the east room was indeed a corner.

There is no ready explanation for a corner being built at this location, or why the original kitchen foundations contained five corners. Had the north wall of the central room ever joined the north wall of the east room, they would have done so with an abutment joint, but there is no evidence to prove it.

A test hole was dug on the southern face of the south foundation between the east and central rooms. The purpose for the test was to see if the brickwork showed any evidence of an abutment joint. If an abutment joint existed, it would be conclusive evidence that the central and west rooms postdated the east room. The bonding pattern was found to be continuous though, 22 which precluded any notion that the east room was the original kitchen. As an added measure, the south half of the hearth base was taken apart so that the bonding of the partition wall and south foundation could be examined. Again, the consensus was that the walls were constructed at the same time.

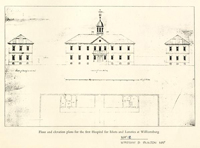

Floor and elevation plans for the Public Hospital found in Wyndham B. Blanton's Medicine in Virginia in the Eighteenth Century 8, may provide some clues as to why a fifth corner was built into the original foundation. (Unfortunately, who drew the plans and in what year, is not known.) The floor plan shows two outbuildings behind the main building and the two detached wings (see map #12). The view is looking south, since the wall which enclosed the hospital grounds appears to be depicted. On the drawing, the kitchen is shown on the east side of the property and the laundry on the west side. This, of course, is wrong; it is exactly the opposite. If the plan is a view looking north, which would place the buildings in proper perspective, then it would indicate that a wall was built in front of the kitchen and laundry. This is very unlikely, and there is no evidence, either written or archaeological, that such a wall existed.

In any case, it is interesting to note that the kitchen is divided into three rooms, and that the central room is depicted 23 as being slightly larger than the rooms on either side. By comparison, the interior dimensions of the central room were approximately 21 by 18 feet. The east and west rooms were 12 by 18 feet and 11 feet 6 inches by 18 feet, respectively. The central room was 9 feet to 9 feet 6 inches larger than the east and west rooms.

The north wall in the drawing of the kitchen shows a doorway at the northeast corner of the central room (see map #13). The position of the door corresponds exactly to the location of the irregular cut of the north wall builder's trench. At the northwest corner of the east room, there appears to be a corner, or return, but the quality of the drawing makes it very difficult to tell with any certainty.

Another interesting aspect of the plan is the possible hearth depicted along the south wall of the central room (see map #13). It was previously stated that a drain box and vaulted brick drain were added to the kitchen during the remodeling period. The drainage system was situated on the interior and exterior sides of the south wall. The south wall builder's trench, located inside the building, appeared to be slightly wider than the other trenches. Two brick features that appeared to be piers were found when the fill was removed. The piers were about 1 foot 3 inches wide and extended 9 inches from the interior face of the wall.

24There was an 8-foot gap between the two piers (see map #14). The gap was filled with bricks that were slightly different in color than those used on the remaining portion of the south wall. It was speculated that the builders, not exactly sure where the drain would enter the kitchen, left a gap in the wall; the open space to be filled in later. This would imply that the drain and the kitchen were built at the same time. However, it is known that the kitchen was built in 1825, and the first documented reference to vaulted drains was not until 1835. The 8-foot section could represent a door opening up onto Ireland Street, but it is unlikely that a door that large would have been used.

Evidence of a hearth in the original kitchen could not be found during the excavations. The gaze in the south wall of the central room strongly suggests that a hearth may have been placed there. When the remodeling of the kitchen was undertaken in 1835 and a new hearth base was built, the old one would have been torn down. The open space left by the demolition of the chimney would have conveniently accommodated a new drainage system. A search along the exterior of the south wall for some evidence of a fireplace was unsuccessful. The two brick piers may be the only evidence left of any such fireplace.

Other features drawn on the plan cannot be substantiated by archaeological excavations, except for the window shown on the far east wall (see map #13). There is architectural evidence that 25 a window was located on this wall. A rectangular window well, postdating the original foundation, was found about midway along the east wall (see map # 5 ).

The floor plan of the kitchen must have been drawn between 1825 and 1835, before the north addition was built. While the validity of the plan may be in question, it is the only known drawing that closely parallels the foundations uncovered during the recent archaeological excavations. If the drawing is accepted as a true floor plan of the 1825 kitchen, then there is room for skepticism about a window being placed on the west wall of the east room. The evidence that supported this statement was based on a brick feature on the fallen west wall that was interpreted as a possible windowsill, and the presence of window glass found in the immediate vicinity. According to the undated drawing, the opening between the east and central rooms appears to be a door instead of a window. It this is the case, then the articulated brickwork is not part of the west foundation, but a remnant of the east wall, and the windowsill and glass are associated with the window well found outside the building. The implication is that the east wall was brought down first and then the hearth brickwork on top of it.

The western third of the kitchen was heavily disturbed by the post-1870 construction, destroying any evidence of builder's trenches. The partition wall that divides the west and central rooms 26 was found bonded into the north and south foundations of the kitchen. Only four courses of bricks were left after the robbing activity. Artifacts recovered from the robber trench fill dated after 1845, while the builder's trench contained material with a terminus post quem of 1785.

The east room of the kitchen contained sections of builder's trenches along the exterior of the north, east, and south walls. The only evidence of a builder's trench found inside the east room was along the south face of the north wall. The trenches were disturbed by the construction of the 1885 Administration Building and the placement of the window wells on the exterior walls. On the average, the trenches were 1 foot wide and about 1 to 2 feet deep. Collectively, the artifacts from the east room trenches indicate that the kitchen was built after 1810.

Most of the builder's trenches throughout the kitchen contain artifacts that date from the latter part of the eighteenth century. While the evidence produced from these trenches clearly points to the fact that the structure is post-colonial, it does not firmly date the construction. Historical records were essential in analyzing the archaeological evidence from the kitchen. It was a known fact before the excavation of the kitchen was undertaken that the building was on top of ravine fill that probably dated to the latter part of the seventeenth century. The 27 ravine was obviously used as a trash dump right up to the time of the construction of the kitchen. Artifacts from the builder's trenches clearly support that fact. The point is, without the historical documentation, interpreting the archaeological evidence would have been more difficult.

KITCHEN EXTERIOR

Exterior features on the kitchen are believed to have been added during the remodeling phase. One of the most important features was a solid brick pier located north of the northeast corner of the kitchen (see map #5 ). The pier was 2 feet 3 inches by 1 foot 9 inches and constructed with red bricks that were the same as those used in the north addition and hearth base. The pier, which is 6 feet from the northeast corner of the original kitchen, lines up with the north wall of the addition. A search for a similar pier at the northwest corner turned up a small section of brickwork that had been disturbed when the cistern was built. Too much of the brick feature was missing to determine with any certainty if it was an identical pier. The bricks, however, were the same as those used in other features built during the remodeling. The piers may be supports for wood porches on either side of the north addition. Unfortunately, there is no concrete evidence which proves that the piers were used in this 28 manner. If wood porches, either open or closed, were attached to the kitchen, the overall dimensions of the building would have been 50 by 28 feet.

Brick paving in front of the north addition suggests that a walkway was laid after the changes in the structure were completed (see map #5 ). The outside edge of the walkway was lined with soldier bricks to keep the bricks from spreading apart. The walkway, which was about 10 feet wide, was found only on the north and east sides of the kitchen. There was no evidence of any walkway on the west or south sides. Along the east wall of the original kitchen, the bricks abutted the side of the foundation and the window well. In front of the kitchen, the walkway abutted a V-drain that was installed on the outside edge of the addition foundation. The V-drain ran along the entire length of the east and north walls of the addition. It then turned toward the southwest and terminated at the junction of an east-west and north-south vaulted drain system (see map #5 ). Water was carried away from the addition by the V-drain and then dumped into the vaulted drains.

Water table bricks were found on the exterior face of the north and south walls, marking where the foundation began to narrow. The angle of the water table bricks appears to have dictated the angle of the V-drain. The inside edge of the drain rested upon the face of the water table bricks (see map # 8). 29 Remnants of two brick window wells were found attached to the foundations of the east room (see map # 5), Both features were cut by later trenching activities. The window well attached to the east wall was constructed with red well bricks and extended about 1 foot 6 inches from the foundation. The interior dimensions of the well were approximately 11 inches wide and 1 foot 3 inches deep. Artifacts from the fill date after 1820. The window well abutting the south wall was also built with well bricks and the dimensions were about the same. There were no datable artifacts from the window well.

In addition, two semicircular brick features were found on the exterior side of the far west foundation (see map #5 ). Although the features were built with red well bricks, they do not resemble the window wells and it is thought that they served some other unknown purpose. Like the window wells, the semicircular features postdate the original kitchen.

Two vaulted drains were uncovered on the south side of the kitchen (see map #1 ). The drain that led from the central room was at least 34 feet in length. It was cut and bricked up after a modern east-west drain was built south of the kitchen. It was assumed that the drain did not extend much further to the south. There was no trace of it on the south side of the later vaulted drain. The drain was set at a steep angle, dropping a little more than 3 feet from the origin at the south foundation 30 wall, to the terminus, 34 feet away. The drain was filled with artifacts dating from 1850, while the builder's trench fill had a terminus post quem of 1830.

The vaulted drain that originates in the east room is thought to be earlier than the kitchen. The builder's trench fill dates the drain no earlier than 1790. The drain was originally 17 feet 6 inches long, but a more recent section was added, making the overall length 28 feet 6 inches. The newest section of the drain is probably one of the two drains mentioned in 1835. The fill from within the drain dated after 1850, which is probably an indication that both drains were in use right up to the time of the destruction of the kitchen complex.

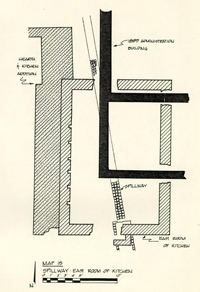

The north end of the drain extended 6 inches inside the south wall of the kitchen. The area around the drain was filled in with mortar and fitted with altered bricks so that the overall bonding pattern of the wall would be consistent (see map #10). A brick run or spillway leading to the drain was found inside the east room during subsequent excavation of the prekitchen layers. The spillway consisted of three parallel rows of half-bricks laid on the same diagonal as the vaulted drain. The spillway was about 1 foot wide and probably more than 4 feet long, but the north end was cut by the 1885 builder's trench. A search for the continuation of the spillway on the other side of 31 the 1885 wall was unsuccessful. However, later excavations near the northeast corner of the 1835 addition uncovered more brickwork that was part of the spillway (see map #15). With the additional section, the overall length of the spillway was more than 21 feet. The origin of the spillway could not be determined, but it was headed in the direction of the early kitchen. It may have carried water down the slope of the ravine to the vaulted drain that ran under Ireland Street. Where the two features met, the top of the spillway was 1 foot 4 inches higher in elevation than the bottom of the vaulted drain. In order to accommodate the spillway, the mouth of the drain was partially bricked up (see map #10). Water ran down the spillway and entered the drain through the 1 foot high open gap. Not only did the partially bricked up drain accommodate the spillway, but it probably prevented erosion from doing structural damage to the drainage system.

The uncovering of the additional section of spillway near the northeast corner of the addition led to an even more important discovery. It was found that the north wall of the original kitchen was built directly on top of the spillway. This would certainly prove that the spillway, and most likely the vaulted drain, predated the original structure.

By the end of 1848, another building, which served as a kitchen-laundry, was constructed near the southeast corner of the 1773 structure. Apparently, the number of patients was 32 increasing at the hospital and additional kitchen facilities were needed. After 1848, the early nineteenth-century kitchen was referred to as the "kitchen-store house." The use of the two detached kitchens, as well as any located in the main building, probably ceased by 1872. A new structure was built that year southwest of the main complex and was reported to contain enough room for a new kitchen, bakery, storeroom, chapel, amusement hall and library.

LATE EIGHTEENTH/EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY KITCHEN

The first documented mention of a kitchen at the Public Hospital was found in the ledgers of Humphrey Harwood, dated June 24 - October 16, 1776. On June 24, 1776, Harwood recorded that 1100 bricks were used to "laying part to kitching floor & layg. harth & mendg. back." 9 According to the initial research report on the hospital prepared by Patricia Gibbs and Linda Rowe, there were no references to outbuildings during the first few years of operations. It was speculated that food may have been brought in from a nearby house or prepared at the Galt Cottage since there were few patients at the time. 10 There is a possibility that food was cooked in the basement of the main building. A kitchen was known to have been in the original structure at least until 1853, when superintendent John M. Galt requested that it be removed. 11 The date of the installation of the kitchen, however, is not known.

The entry in the Harwood ledger does not specify whether the kitchen is in the main building, or if it is a separate/detached structure. The first hint of a detached kitchen is not found until September 19, 1808, when it was recorded that "under silling Kitchen 60 feet" was done by Richard Garrett. 12 The implication is that a kitchen, seated on sills, was located somewhere on the property.

34Other recorded references to a kitchen, prior to the 1780s, include mends to the chimney done on October 16, 1776, and March 31, 1779. Another entry in the Harwood ledger dated July 16, 1779, states that an oven was built at the "Madd House." 13 This oven may be the one ordered by the directors of the hospital at their meeting on August 3, 1778. 14 Additional written references to the kitchen do not occur until 1786.

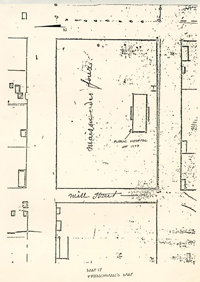

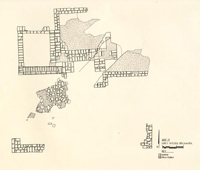

On the Desandrouins map of the town of Williamsburg, dated 1782, a small detached structure can be seen at the southwest corner of the main building (see map #16). On the other hand, the Frenchman's map shows the outbuilding at the southeast corner (see map #17), While the small building depicted on both maps may represent the kitchen referred to in the documents dating before 1780, there is nothing that identifies it as such. The location of the detached kitchen was not revealed in the documentary sources until 1821. Insurance policy #1640, dated May 25, 1821, shows a building at the southwest corner of the 1773 structure. The building is identified as a 36 by 30-foot one-story kitchen made entirely of wood. According to the drawing on the policy, it would appear that the east-west dimensions are 36 feet, while the north-south are 30 feet. The policy further states that the kitchen was within thirty feet of the main building. While there is no conclusive evidence, the building depicted on the Desandrouins map may be the same detached kitchen mentioned in 1308 and the one insured in 1821. If it is not the identical building, it is, at least, one built on the same site.

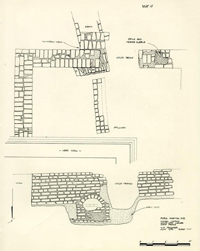

35Archaeological excavations southwest of the 1773 building revealed remnants of what is thought to be the kitchen seen on the Desandrouins map and the one mentioned in the 1821 insurance policy. Kitchen-related brickwork, such as a hearth and possible oven foundation were found, but without any trace of the four exterior walls of the building itself. The kitchen is believed to have been seated on sills or piers that were placed directly on the ground. There was no evidence of builder's trenches or any indication of robbing activities that would prove otherwise.

According to information on the 1821 insurance policy, the kitchen was made of wood. This was confirmed in 1825, when Thomas Lucas was paid for "Planking (the) outside of (the) Kitchen."15 A wood structure of this nature would have been seated on wood or brick sills, if not piers. Unfortunately, there is no archaeological evidence or written sources that could verify it. Even if the kitchen had been seated on brick foundations, they obviously were not substantial enough to leave any trace of their existence. Post holes were found in the immediate vicinity of the kitchen-related brickwork, but none would line up in any semblance of a building. The earliest kitchen-related feature was the fireplace, which was two bricks wide and bonded with shell mortar (see map #18 ). It was probably situated on the south wall of the kitchen since the back of the hearth faced in that direction.

36The overall dimensions were 9 feet 9 inches east-west by 4 feet 8 inches north-south. The open area where the fire would have been was 6 feet 6 inches by 3 feet. The size of the hearth strongly suggests that it belonged to a kitchen. Creamware was the latest ceramic type found in the builder's trench, which would place the construction of the hearth after 1770.

Two brick piers, or footings for the chimney, abutted the back of the fireplace (see map #18). The footings, set 3 feet apart, were seated within the builder's trench for the fireplace. They were built with the same type of brick and mortar that was used in the construction of the fireplace. Each footing was about 1 foot 8 inches square.

The hearth floor was enlarged at a later date when a one-brick wide enclosure was added to the north face of the original fireplace (see map #18). The floor space was increased to 6 feet 6 inches by 5 feet 3 inches. Remnants of the floor were found within the perimeter of the original hearth and the later enclosure. While most of the floor had turned to rubble, three whole bricks were still in position at the southwest corner. The removal of the damaged floor revealed successive layers of rubble, ash, and charcoal. The rubble was probably used to support the hearth floor. The presence of creamware indicates that the rubble and ash layers were deposited after 1770.

37Another brick feature abutted the west side of the original hearth. The foundation is thought to be a bake-oven and is perhaps the one ordered by the hospital directors in 1778 and built by Harwood in 1779. The width of the north and south foundations of the oven are one and a-half bricks, while the west wall is only one brick wide. The west side of the original hearth and the west chimney footing comprise the east wall of the oven (see map #10). The interior of the oven was 4 feet by 4 feet 9 inches.

Builder's trenches could not be found for either the oven or the extension to the hearth. Apparently, both features were seated directly on the ground. It is certain that the oven postdates the hearth, and it could even be the one built by Harwood in 1779. If this is the case, then the hearth had to be built prior to July 16, 1779. There is a possibility that this hearth is the same one that was recorded in the hospital records on June 24, 1776. The artifacts that were recovered from the builder's trench may lend some credence to this assumption.

According to the records, a shed was attached to the kitchen. On September 19, 1808, it was recorded that Richard Garrett spent 2 ¼ days "Repairing Kitchen & shed." 16 Another reference to the shed was made on May 23, 1812, when John Bowden built shelves in "the shed of the kitchen." 17 In a list of extra work done at the hospital in 1825 by Thomas Lucas, the shed 38 was mentioned for the last time, probably due to the fact that plans to build a new brick kitchen were underway.

Foundations, or brick sills, for the shed were uncovered south of the early kitchen features (see map #19). The brickwork indicates that the dimensions of the shed must have been roughly 12 by 21 feet. The probable north foundation of the shed was found immediately south-southeast of the original fireplace. The wall contained what appeared to be a secondary hearth. In addition, the southwest corner of the shed foundation was found intact, along with a portion of the southeast corner. Both sections of brickwork in the corners were partially robbed out. The shed, like the kitchen, was more than likely made of wood, and the brick foundations were used as support for the structure.

The interior of the southwest corner contained a 1-foot section of the west wall and a 4-foot section of the south wall (see map #19). The brickwork at the southeast corner was probably a 3-foot section of the east wall. The greater portions of the east and west walls had been robbed out. Hand-painted pearlware found in the trenches date the robbing activity after 1785.

The robber trench for the south wall was extremely difficult to detect. Only a portion of the trench leading from the southwest corner could be found. The trench extended about 39 3 feet beyond the end of the brickwork where it was cut by a modern hole. There was no trace of it on the other side of the hole, nor was there any evidence of a trench leading from the brickwork at the southeast corner. It was thought that perhaps the supporting foundation never extended completely across the southern end of the building. The south end of the foundation could have been left partially open to be used as a crawl space. Since the kitchen was built very close to the edge of the ravine, the shed would have partly extended down the slope. For the shed to be level, the ravine would have either been filled in, or the southern end of the structure would have been shored up with posts or piers of some sort. The presence of the brick foundations on the upper slope of the ravine would suggest the latter. In order to provide a level surface for the shed, the height of the south wall, as well as part of the east and west foundations, would have been greater than that of the north wall. If these foundations were indeed higher, then it would be reasonable to expect them to be wider also. Apparently, this was the case because the north wall was 8 ½ inches wide, while the brickwork at the southeast and southwest corners was 1 foot 3 inches.

A 6 foot 6-inch section of the north wall was located south-southeast of the original hearth (see map #18). The wall was one brick wide and bonded with shell mortar. As the wall neared the east chimney footing, it turned a right angle to the 40 south for a distance of 2 feet 2 inches. It then turned due west for about 2 feet where it was cut by a modern utility trench. Another 10-inch section of the wall was found on the south face of the west chimney footing. The west half of the north foundation was apparently robbed out.

The manner in which the brickwork is positioned behind the original fireplace suggests that a secondary hearth was in use inside the shed. The chimney footings were apparently used as backing for the fireplace. The interior dimensions of the hearth were 5 feet 4 inches by 1 foot 7 inches. Builder's trenches could not be found for any of the later brick features and the hearth was heavily disturbed by the utility trench.

The date of the construction of the kitchen addition is not known, but the first reference dates at least 1808. The earlier kitchen and attachment were obviously torn down after the 1825 facilities were built; however, there are numerous references dating between August 24, 1825, and July 1826, to an "old kitchen" and a "new kitchen." These references would indicate that the kitchens were standing at the same time (see map # 1) for a view of the kitchen foundations). It was reasonable to assume that the older kitchen would have been torn down shortly after July 1826, but on June 20, 1828, Dickie Galt was ordered "to proceed to have . . . a roof put on the old kitchen, 41 (and) repairs made to the enclosure . . ." 18 This was the last mention of the earlier kitchen in the historical records.

A 1 foot 5 inch to 2-foot layer of redeposited yellow, orange, and grey clays (E.R.2962J-4C, E.R. 2963L-4C, E.R. 2966V-4C, E.R.2967N-4C, and E.R.2549W-4C) sealed and abutted the southern portion of the kitchen addition foundations. The mixed clay layer contained lenses of brown and grey silt with mortar and orange brick fragments. The presence of banded pearlware crated the deposit after 1810. The clay did not extend very far north of the foundations, although it completely sealed the east-southeast brickwork and, for the most part, abutted the south face of the southwest corner.

The clay must have been deposited after the early kitchen was brought down, but prior to the construction of the north addition of the 1825 kitchen. The exterior builder's trench for the 1835 addition cuts the clay layer (see map #8 ). The same clay could not be found inside the 1825/1835 kitchen complex and, therefore, it seems likely that the material was deposited so that the brick walkway around the later kitchen would be level with the terrain to the north. The kitchen floor was raised when the 1835 addition was built, so it must have been necessary to fill in and level off the area between the addition and the old kitchen.

42The destruction of the early kitchen may be represented by a layer of brick rubble (E.R.2962H-4.C., E.R.2963H-4.C., E.R.2963J-4.C., and E.R.2963K-4.C.) found tightly contained within the area of the shed. Since the kitchen and shed were constructed of wood, the rubble is probably debris from the demolition of the hearth, oven, or the foundations. The rubble might also be debris from the numerous repairs made on the hearth and oven. A penny found in the rubble layer dates the demolition or repair work after 1820.

The removal of the rubble layer exposed a grey silt layer (E.R.2962L-4.C. and E.R.2963P-4.C.) that was found only between the two southern sections of brickwork. The silt was 1 foot 11 inches wide north-south and 8 inches thick at the most. The important aspect about the layer is that it appears to have come about only as a result of the removal of the south foundation wall, or some other barrier. The silt filtered down the embankment left behind when the south wall or barrier was removed.

There was more evidence of a wall along the south end of the shed when a layer of clean yellow sand (E.R.2962M-4.C. and E.R.2963R-4.C.) was found beneath the grey silt. The yellow sand began at the embankment and extended down the slope of the ravine 3 feet 11 inches. This was the same sand found below the 43 thick layer of redeposited clay. The sand may have been put down as a leveling agent for the south foundation of the shed. Since the sand extends beyond the 1 foot 3 inch limit of the brick work, it may be an indication that the foundation was seated directly on the ground surface. Erosion, before or after the wall was robbed out, carried the sand down the slope of the ravine. If it was not necessary to dig a builder's trench to seat the wall, then it would explain why a robber's trench could not be found.

Behind the early kitchen was a 4 inch to 1-foot thick layer of dark grey silt and oyster shells containing a great many artifacts (E.R.2962T-4.C., E.R.2963W-4.C., E.R.2966Z-4.C., E.R.2967S-4.C., and E.R.2997G-4.C.) This rich layer dated from 1785 to after 1820, and was probably deposited during the life of the building. In addition, three more layers contemporary with the kitchen were found south of the earlier foundations. The layers were contained within the area of the shed and could not be found further down the slope of the ravine. Underneath the rubble mentioned previously, was a 1/2 to 3-inch layer of reddish-brown and grey silt (E.R.2962N-4.C. and E.R.2963S-4.C.) with another 4 to 6-inch deposit of medium grey silt (E.R.2962R-4.C. and E.R.2963T-4.C.) immediately below it. A crossmend of artifacts from the two layers shows that they are contemporary and the presence of hand-painted polychrome pearlware dates the 44 deposits after 1795. A third layer of light sandy grey silt mottled with yellow sand (E.R.2962S-4.C. and E.R.2963V-4.C.) was located directly below the other two layers. Although the artifacts from this layer date after 1750, the deposit can be found only in the same tightly contained area as those above it. A preliminary crossmend of the creamware did not reveal any relationship between the features associated with the original structure and the early kitchen layers on the slope of the ravine.

STRUCTURE ON THE EAST SLOPE OF THE RAVINE

In August 1981, heavy machinery began clearing the southeast sector of the Public Hospital site. The purpose of the clearing operations was to determine the natural east slope of the ravine, as well as to locate any structures that may have existed south of Ireland Street. As the machinery worked toward the southeast corner of the sub-pen foundation, the slope of the ravine became apparent. Layers of fill not found further to the north began to appear as the excavations progressed down the slope. The tip of the ravine fill began about 50 feet north from the southern limit of excavation.

An area bordered on the west by the sub-pen foundation and on the south by the courthouse property was given an arbitrary number (E.R.2661-4.C.) when a heavy concentration of brick rubble began to appear. The area was approximately 29 feet east-west by 22 feet north-south. The heavy concentration of rubble (E.R.2661A-4.C.) was thought to be debris from the 1885 fire. The east-west section along the southern limit of excavation showed that the layer of rubble, slate, marble, and mortar was about 3 feet thick. A 3-foot layer of topsoil and redeposited clay (E.R.2661A-4.C.) was on top of the rubble. The 1885 debris was cleared from the site by machine.

46A layer of brown loam mixed with brick and mortar fragments (E.R.2661C-4.C.) was found beneath the 1885 rubble. The 1 to 3-inch layer of fill contained artifacts that dated no earlier than 1820. A second layer of redeposited clay with brick and mortar fragments (E.R.2661D-4.C.) was under the brown loam layer. The clay layer measured 9 to 10 inches at the southern limit of excavation and dated after 1850.

The stratigraphy at the southern limit of excavation showed that almost 7 feet of fill had been removed before a second layer of rubble (E.R.2661E-4.C.) was discovered (see map #20A). The rubble, believed to be the destruction debris from the 1805 Convalescent House, was about 2 feet 3 inches thick along the east-west section. Whiteware found among the artifacts dated the layer after 1850. Elevations taken at the north and south limits of the rubble, show that the slope of the ravine dropped more than 4 feet.

The second layer of rubble was partially excavated before a grid was laid out. The possibility that a building was taking shape required that a grid be put down for better control. The remainder of the rubble was excavated according to balks and squares. The removal of the debris exposed the outline of a possible building cut into the side of the ravine.

47A tip of redeposited clay was excavated along the north and east sides of the possible structure. A ninety degree cut into the subsoil was found after the clay layer was extracted (see map #20B). Apparently, the subsoil was cut to accommodate the north and east foundations of the building. When the walls were robbed out, the clay was thrown in to fill up the hole. No datable material was found in the clay layer.

According to the robber trenches, the interior dimensions of the structure would have been approximately 12 feet east-west. The trench for the south wall could not be found due to the limit of excavation; however, the building was at least 16 feet north-south (see map #20). The robber trenches were 1 foot 8 inches wide and from 2 to 9 1/2 inches deep. The latest artifacts found in the fill date after 1850.

The floor of the building was seated on 8 ½ inches of redeposited clay, industrial clinkers and yellow sand (see map #20B). The leveling agents were contained within the boundaries of the robber trenches. The presence of the yellow sand probably indicates that the floor was brick.

There were no physical remains of the structure that could verify whether or not it was made of brick, nor was the function of the building determined with any certainty. Due to 48 the large quantity of bones found in the rubble layer, it was speculated that the structure may have been used as a meat house. However, references to a meat house could not be found in the historical records. The robber trenches may indicate that the foundations of the building were two bricks wide, which would support at least a story and a-half structure. Crossmends between the robber trenches and the layers of fill that sealed the building show that they were deposited at about the same time. If not, the layers were heavily disturbed during the robbing activities.

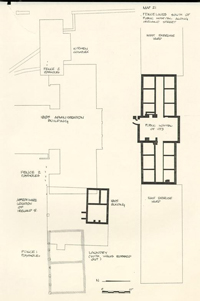

THE SOUTH BOUNDARY LINE

To the southeast of the 1805 Convalescent House, seven post holes were found in the bottom of the robber trench for the 1848 kitchen/laundry (see map #21). The postholes ran in an east/west direction with the molds approximately 8 feet apart. The postholes are probably part of the south boundary line of the Public Hospital property. In 1773, Benjamin Powell was contracted to impale all of the hospital lots. The line of postholes, which are parallel to and north of Ireland Street, are thought to be part of the impaling fence. Artifacts found in the post molds and postholes date from the last quarter of the eighteenth century. The historical records also indicate that the fence line was repaired several times. Archaeological excavations showed that many of the postholes were repaired or replaced as many as four times.

The seven postholes represent at least 48 feet of fence line. The full extent of the impaling could not be determined due to the limit of excavations on the east and later remodeling and construction activities on the west. However, a second series of holes were found approximately 24 feet west of the 48-foot long section of impaling (see map #21). These holes were not on the same alignment with the fence line to the east, but appeared to be situated slightly to the south. The holes may not necessarily be part of the original fence or 50 impaling line, but repairs or replacement holes, which would account for the misalignment. All but one of the postholes contained pearlware, which would date the features anywhere from 1785 to after 1820. The remaining posthole contained creamware. Signs of any postholes lying between these postholes and the 48-foot long section of fence line probably disappeared when the 1805 Convalescent House was enlarged.

For the next 92 feet, the area was heavily disturbed by the 1885 Administration Building addition, utility trenches, and the 1825 kitchen. Two holes found inside the east room of the 1825 kitchen might have been part of the fence line. The holes were on the same line as the second series of portholes found on the east side; however, a terminus post quem could not be established with any certainty because there were no ceramics found in the fill. The only thing known about the postholes is that they predate the kitchen.

The wood fence was no longer in use by the end of the 1830s. On April 10, 1838, a committee was appointed to advertise for bids to build a brick wall around the Public Hospital. The wall was to be "about five hundred yards in length, ten feet high, besides the coping, including two feet in the ground." 19 The wall would have been north of and parallel to Ireland Street, separating the hospital property from the road (Ireland Street 51 was not purchased from the city until 1867). The committee eventually requested and received from the Virginia Legislature $5,000 for the project in 1839. On March 1, 1842, it was reported that the account for building the wall had been paid in full, costing a total of $4,466.50. 20 Archaeological excavations did not uncover any evidence of this brick wall.

A crossmend of the artifacts from the 1825 kitchen and the test trench along the west slope of the ravine was undertaken. A great deal of pearlware came from the test cut and the purpose of the crossmending project was to find out if the artifacts were associated with the kitchen. While the material from the kitchen was very similar in type and pattern to that of the trench, there were no mends. Apparently, the artifacts in the trench came from a completely different source. The most likely source would have been the Galt Cottage which was on the south side of Ireland Street. The wood impaling, or brick wall which separated the hospital property from Ireland Street, may have prevented any kitchen debris from filtering down the slope of the ravine. If the artifacts found on the west slope of the ravine are associated with the kitchen, it would mean that the material was carefully deposited there and that not even the smallest piece of ceramic was inadvertently left north of the enclosure.

According to the records, the brick wall surrounding 52 the hospital property was to be 500 yards in length, which would make each side 375 feet long, provided that the enclosure was supposed to be square. There are no documents, nor any archaeological evidence, which suggests that the walls were of equal length. The unsigned and undated elevation and floor plan of the hospital does, however, show the entire south fence line, along with part of the east and west walls (see map #12). Using the 1825 kitchen shown on the plan as a scale, the south wall measures close to 375 feet. The other walls would have to be of equal length in order for the entire enclosure to be 500 yards long. According to this layout, the enclosure did not quite reach Henry Street and it was more than 60 feet away from Francis Street (see map #22). The enclosure shown on the drawing does not necessarily have to be the brick wall, but could very well be the impaling line. The brick wall was not put up until 1839 at the earliest. Since the plan does not show the north addition of the 1825 kitchen, which was built about 1835, the wall is more than likely the impaling line. In any case, it shows that the hospital property enclosed by the fence line was at least 375 feet square.

JONES/NICHOLSON LAYERS

Occupation levels that predate the 1773 building have been termed the "Jones/Nicholson layers"; named for two individuals who were associated with the property before the hospital was built. The occupation layers were rather extensive and concentrated mostly in the vicinity of the ravine, which became a natural dumping ground for the occupants of the property. In the majority of the cases, it was difficult to identify a "Jones layer" versus a "Nicholson layer" because of the churning effect that took place as artifacts and silts travelled down the slope of the ravine. Artifacts from both periods tended to blend together as erosion shifted the layers.

Aside from the balk in the Jones cellar and the late seventeenth-century trash pit located southwest of the 1805 Convalescent House, most of the archaeological excavations took place along the upper edges of the ravine. Mr. Nick Luccketti dug the head of the ravine in the winter-spring of 1980-81, and Mr. John Hammant investigated an extensive area east of the kitchen complex in the summer of 1981. In each case, the excavations uncovered layers, features, and artifacts dating from the early to mid-part of the eighteenth century.

While the excavation of the pre-hospital features along the edge of the ravine was underway, modern layers and intrusions were cleared from the "sub-pens" by heavy machinery. Each "sub-pen" 54 or bay was approximately 67 feet long (north-south) by 11 to 12 feet wide (see map #1). The pre-hospital layers in the east bay were confined to a small area at the extreme southern end, while the middle bay was heavily disturbed by a vaulted drain that ran down the middle. The excavation of the west bay showed that the pre-hospital layers had been turned over in the same manner as those near the edge of the ravine. For example, a layer given a terminus post quem of 1770 could be found sealing one containing pearlware. There were, however, a few layers just above the subsoil that did date around the first quarter of the eighteenth century.

Generally speaking, the "Jones/Nicholson" level could be readily identified from the hospital strata by the color of the soil seen in the profile. The early layers were medium to dark grey in color and were sealed by hospital period fill that contained clay in varying degrees. On the other hand, the prehospital fill contained mostly silts and ash and very little, if any, clay.

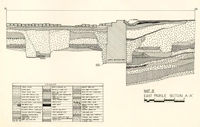

Completing the excavation of the kitchen complex took longer than anticipated, leaving very little time to thoroughly examine the pre-hospital layers. Before heavy machinery arrived on the site to start clearing operations, it was decided that a trench should be cut across the upper slope of the ravine. The trench, which was to cut through the middle of the nineteenth-century kitchen, would serve two purposes. First of all, the 55 profile would show the hospital and pre-hospital stratigraphy and, secondly, the natural slope of the ravine could be determined. By mechanical means, a trench, oriented east-west, was cut about 120 feet long, 6 feet wide, and 5 to 12 feet deep (see map #23).

The trench revealed some surprising aspects about the stratigraphy. The hospital layers were found to be more substantial than they were previously thought to be. In some cases, there was more than 5 feet of fill lying above the grey "Jones/ Nicholson" level and the south half of the kitchen foundations were at least 2 feet away from reaching the early layers. The foundation of the east room and the hearth base were seated on a layer of fine, clean, grey silt that was about 18 feet wide (east-west) and 2 feet thick at the deepest point. The layer may have resulted from natural silting, but it seems more likely that it was dumped there in order to fill in the ravine. The trench also revealed the natural slope of the ravine, which was expected to drop sharply on both sides in a U-shaped manner. Instead, the profile showed that it was a gentle slope.

Clearing operations prior to the construction project prevented any further excavations. Some of the "Jones/Nicholson" fill was trucked to the dump site where it was sifted for artifacts.